NEWS

26 Oct 2021 - Investment Perspectives: Don't fear the taper

|

Investment Perspectives: Don't fear the taper Quay Global Investors October 2021 |

|

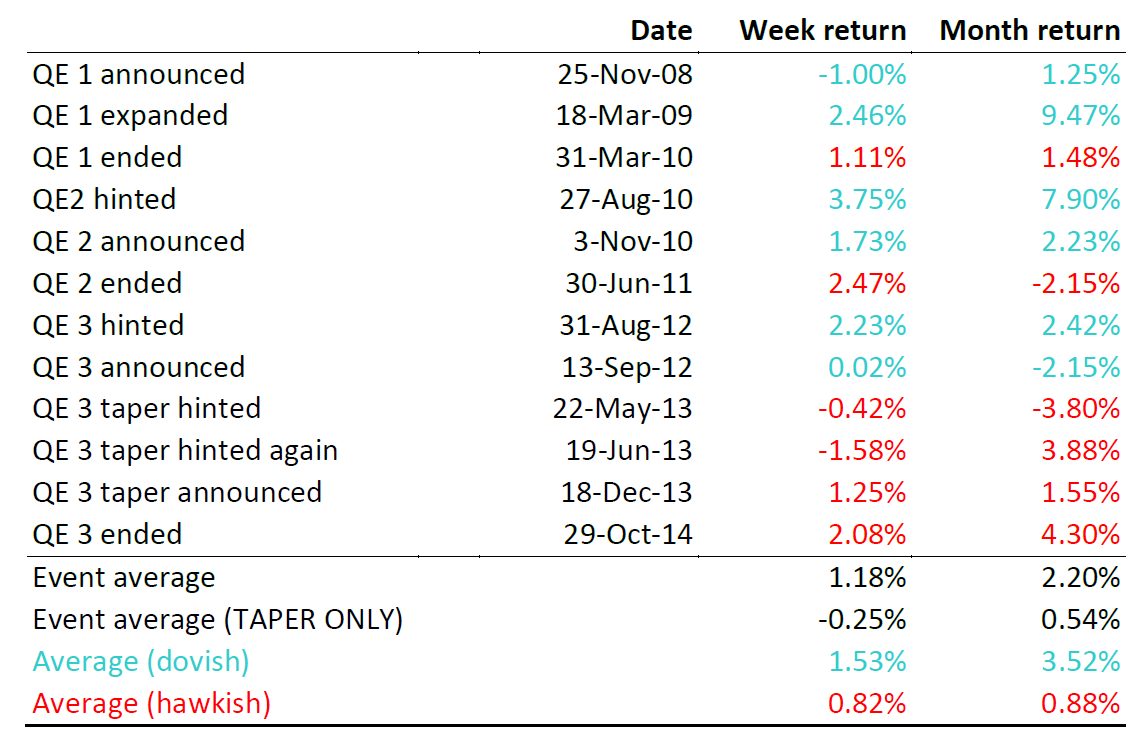

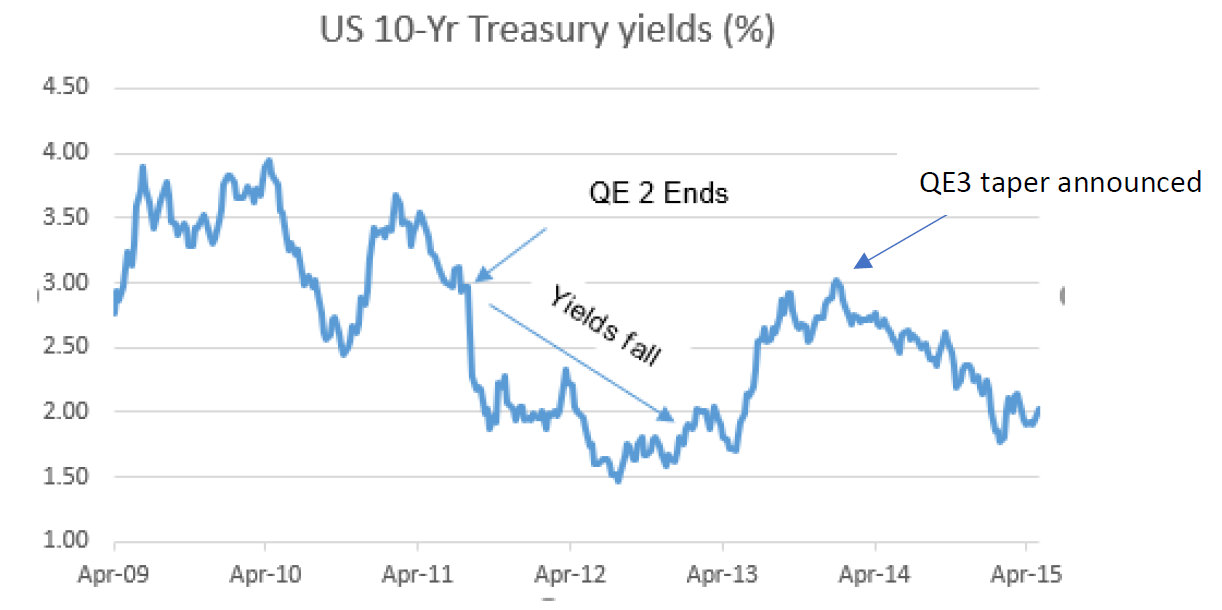

As vaccination rates increase around the world and we (hopefully) return to some normality in our daily lives, world economies appear to be stabilising. Economic output is near or above pre-pandemic levels, and signs of inflation and wage pressure have become a theme of 2021. As a result, many investors and commentators are now keeping a close watch on the US Federal Reserve and any change in current monetary policy: specifically, the quantitative easing program (QE) and the potential that the monthly asset purchases (US$120bn per month) will begin to slow, or 'taper'. Some investors have bad memories from the last time the US Fed tapered, and as such there appears to be some anxiety over the next central bank move. Indeed, in the minutes from last month's meeting, the committee stated, "Most participants noted that, provided the economy were to evolve broadly as they anticipated, they judged that it would be appropriate to start reducing the pace of (asset) purchases this year".[1] Should investors fear the taper? Some historic perspectiveSince the great financial crisis of 2008/2009, there have been three QE programs in the United States: two of which ended abruptly, and the third via taper (a gradual reduction in monthly asset purchases). The following table highlights the dates of each announcement (or signalling) of these policies, and measures the performance of the S&P500 Index in the week and month following these announcements.[2]

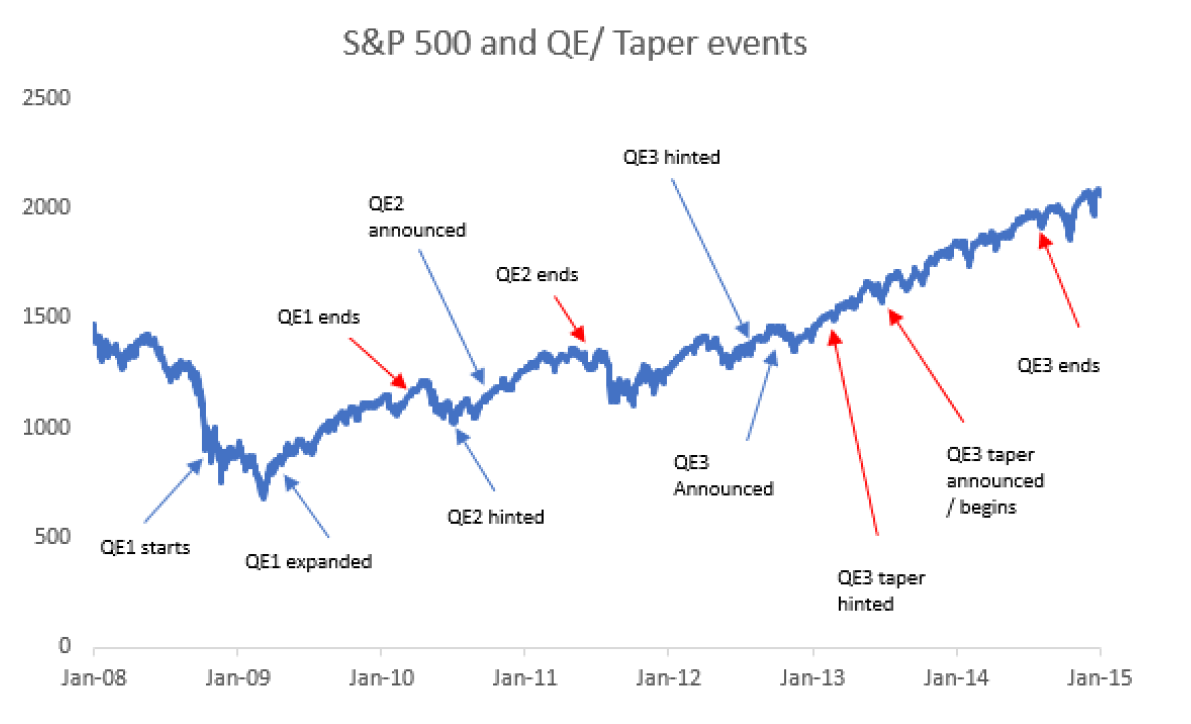

Source: Calculated Risk, Bloomberg, Quay Global Investors To assist our analysis, we have colour-coded each 'QE event' depending whether the policy announcement was dovish (supportive of the economy and more QE) in blue, or hawkish (restrictive and less QE) in red. The taper - which was first hinted at in a speech by Ben Bernanke on 22 May 2013 - set a clear path to the end of QE and led to the first post-GFC rate increase in December 2015. The data clearly shows a 'dovish' Federal Reserve tended to be good for stocks over the following week and month (on average up +1.53% and +3.52% respectively). However, it is also clear the end of QE (on average) is not necessarily bad for equities (on average up +0.82% and +0.88%). Most of the taper angst appears to be derived from the May 2013 statement to US congress by then-Chairman Ben Bernanke, when the concept of gradually reducing asset purchases was first suggested.[3] Unlike the end of the first two QE programs, this signalled a change in policy, and introduced 'the taper' for the first time. Yet in the current environment, this moment has already passed as per the September minutes. And based on historic performance, the idea that we should worry about any taper carries very little historic weight. Moreover, for investors not concerned with short-term performance, the best strategy post-GFC was to ignore the taper/QE noise entirely and simply stay invested.

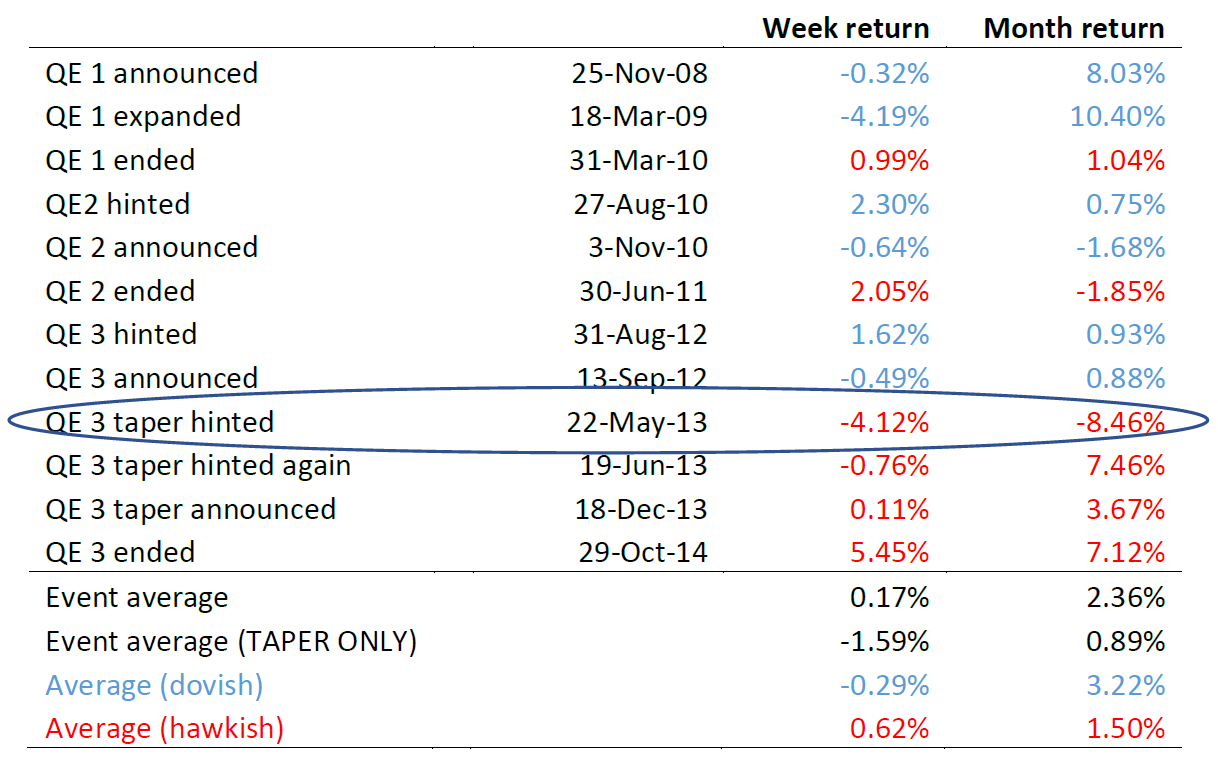

What about real estate?Listed real estate was not immune to the volatility caused by various quantitative easing announcements. However, the data again suggests there is little to fear with respect to any end to the QE program - although admittedly, there was more volatility. It would probably surprise some investors that global real estate did worse over the week after the Fed was dovish (-0.29%), compared with when it was hawkish (+0.62%). And like the S&P500, on average global real estate actually performed well in the month following the various taper announcements (+0.89%), and following hawkish statements (+1.50%) .

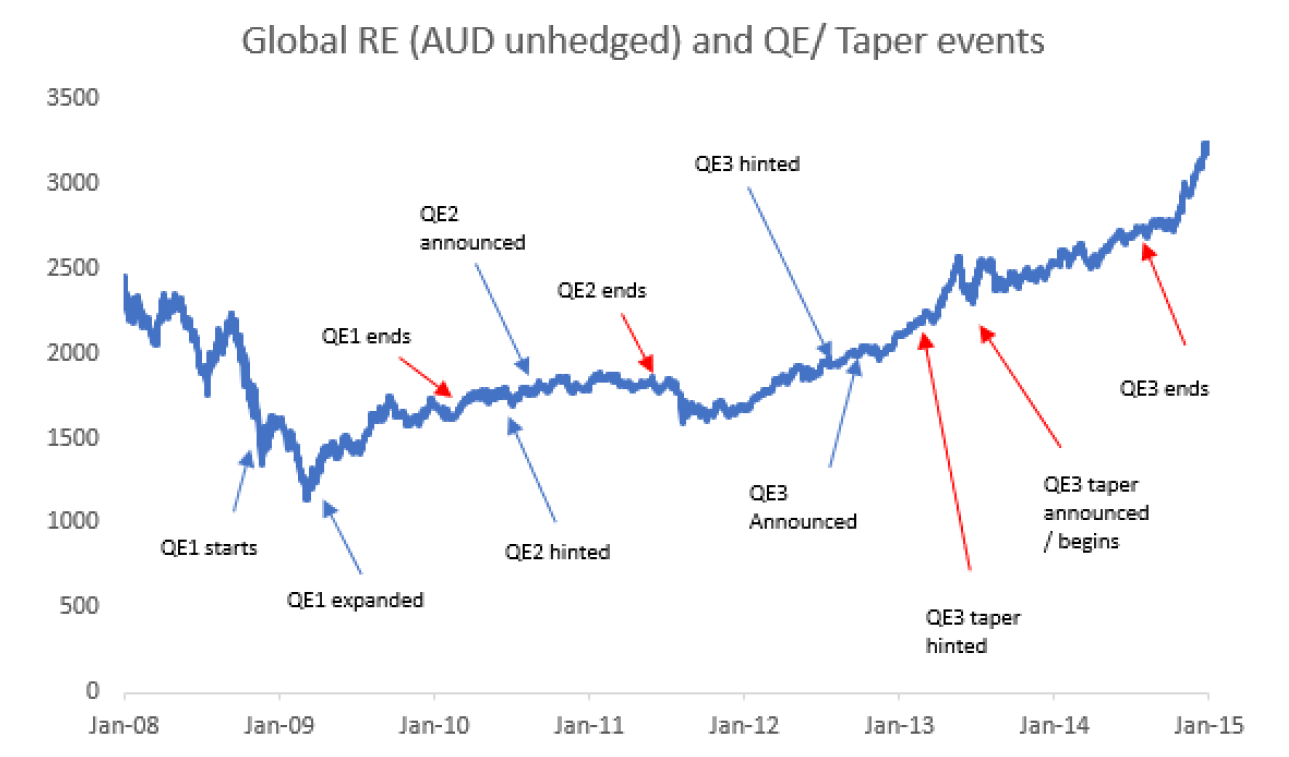

Again, as the following chart shows, long-term investors in global real estate that ignored the noise were rewarded over time. We also make the observation that global listed real estate performed best during and after the Fed became consistently hawkish following the initial taper hint in May 2013. This again should remind investors that real estate does best when the economy is good, not when interest rates are low (or central banks are dovish). For more on this, refer to our 2019 article 30 years of investment lessons from Japan.

Source: Bloomberg, Calculated Risk, Quay Global Investors Why QE has less impact on equity markets than most thinkA common narrative post financial crisis was that various central banks (across the world) influenced equity markets directly or indirectly with their various monetary programs - especially quantitative easing. Throwaway lines such as "flooding the market with liquidity" or "artificially reducing interest rates" or "forcing investors into risky asset" played well with the CNBC/Zero hedge crowd, but rarely are these comments scrutinised for the detail. The reality is that central bank influence on equity markets valuations is minimal at best, for the following reasons.

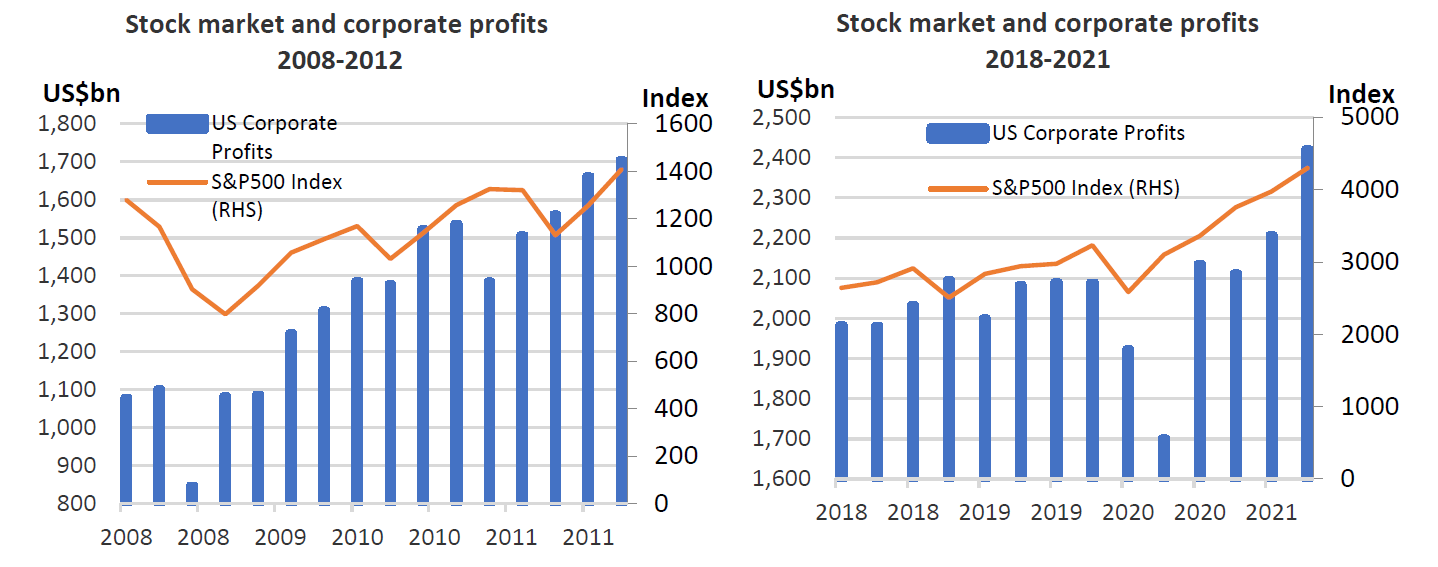

It's all about profitsAs we have stated in previous articles, what drives long-term equity returns are profits. And while some investors blame (or credit) central banks for share market performances, on most occasions equity performance is supported by rising earnings. As we highlighted in our June 2021 article checking in on Kalecki, the macroeconomic source of company profits is more closely aligned to fiscal policy (spending and taxing), not monetary policy.

Concluding thoughtsAt Quay, we are unapologetic in our bottom-up approach. This does not mean we ignore macroeconomic data or various government policy. The key is understanding which macroeconomic issues matter. The US has now enacted various forms of QE over the past 12 years - and not unlike the Japanese experience (now 20 years of QE), the data suggests worrying about central bank policy and actions is not productive for long-term investors. That's not to say equity markets are not overvalued; but if they are, it has more to do with animal spirits than the Fed. Our observation is investors should spend less time worrying about central bank actions that have very little impact on equity markets beyond a placebo effect - and more time remaining invested in high quality companies that grow cashflows sustainably over time. |

|

Funds operated by this manager: Quay Global Real Estate Fund |

26 Oct 2021 - The Winter of Discontent

|

The Winter of Discontent Arminius Capital 12 October 2021 The winter of 1978-1979 was disastrous for the UK economy. A combination of freezing weather, rising inflation, union wage demands, and public and private sector strikes caused fuel shortages, food shortages, and essential services failures. The press christened the period "the winter of discontent", borrowed from the first line of Shakespeare's Richard III. Not surprisingly, Margaret Thatcher won the May 1979 election. The coming winter of discontent will affect much of the northern hemisphere, but particularly the UK and China. The US is all but self-sufficient in energy, although it will continue to suffer supply chain disruptions. The EU has sufficient spare generating capacity and cross-border electricity transmission to mitigate the power problems, and Russia has promised to step up gas supply. India has managed to create its own coal shortage without having a Communist Party or a Conservative Party to make mistakes, but very few global investors have any exposure to the Indian share market. Boris Johnson doesn't have to face a general election until May 2024, but the winter of 2021-2022 is shaping up as a major public relations disaster for his government. Rising oil, gas, and commodity prices are exacerbated by higher transport costs, not to mention labour shortages in essential functions such as truck drivers, butchers, and process workers. Lack of truck drivers has forced the government to use the army to deliver petrol to service stations, and supermarkets are already suffering stock-outs of basic items such as eggs, milk, pasta, and canned fruit. The shortages have been blamed on COVID-19, Brexit, EU bloody-mindedness, UK government incompetence, private sector inadequacies, and global supply disruptions. What is clear is that there are no quick solutions. Xi Jinping is facing the same types of problems in China: power cuts and supply disruptions. The nationalistic (State-owned) media has blamed these on the usual suspects - corrupt officials, foreign saboteurs, counter-revolutionaries, and "bad elements" generally - but in China's case the true causes are well-documented. Demand for Chinese goods surged in 2021 as the global economy recovered. This meant that demand for electricity surged. But more than half of China's electricity comes from coal-fired plants, and since 2016 the central government had been forcing the closure of small coal mines, not in a quest for net zero emissions, but because of the very high levels of local pollution and industrial accidents in these small mines. Alex Turnbull makes a persuasive argument that part of the shortage was caused by the disruptive effects of anti-corruption campaigns in Inner Mongolia - see https://syncretica.substack.com/p/rectification-campaign-to-energy. So China needed more electricity than it had the coal to produce. The obvious next step was to import more coal. Unfortunately, the rest of the world wanted more coal too, so prices had already risen sharply. To complicate matters, in 2019 the central government had unofficially halted thermal coal imports from Australia, and the spare Australian coal had been sold to other countries. By mid-2021 it was clear that many Chinese provinces did not have enough electricity to power their economies. Yunnan, for example, has built an aluminium industry on cheap and abundant power from its hydro stations. But in 2021 low rainfall reduced hydro power supply, so Yunnan was forced not only to shut down alumina smelters, but also to reduce electricity exports to the neighbouring province of Guangdong. What made matters worse is that, because two-thirds of China's provinces had missed their targets for reducing energy consumption and energy intensity, the central government told cities which were home to major polluters to shut down the worst offenders for several hours a day or a few days each week. This means heavy industries such as steel, cement, glass, and paper manufacturers. Another complication: local power prices are set by the government, usually for the benefit of industrial and residential users. When higher coal prices pushed coal-fired power stations into losses, most governments would not agree to any power price rises. In response, generating companies stopped buying expensive coal and temporarily shut down their unprofitable power stations. Xi Jinping and his Politburo are several management levels above the grassroots, and bureaucrats are never keen to bring bad news to their bosses, so the extent of the problems did not become obvious until September. The eventual response shows that - unlike Boris Johnson - Xi Jinping took matters very seriously indeed.

INVESTMENT IMPLICATIONS Whatever happens in the UK will have very little impact on Australian investors. As a trading partner, the UK is slightly more important to us than Thailand. Ever since the Brexit vote in June 2016, the UK share market has traded at a 20% discount to other developed markets, so a lot of bad news is already priced in. By contrast, the power cuts in China are globally important, reinforced with the property market turmoil caused by the Evergrande default. The net effect will be to reduce China's GDP growth rate below 4% annualized over the next six months. Chinese imports of Australian iron ore will fall by 10% over this period, but Chinese imports of Australian thermal coal will rise unobtrusively. The Chinese factory shutdowns will add to the world's supply shortages and keep commodity prices weak until the Chinese economy is visibly back to normal - probably by March 2022. China's power outages will worsen global supply chain disruption, but the key factor which will end the US import shortages is consumers reducing their spending on goods and switching to spending on services. For China's share markets, the impact of the power cuts is negative, but it is far smaller than the damage done to China's tech giants already by the central government's regulatory crackdowns. Because Australia is already on the receiving end of China's unofficial trade war, the downside for us is minimal. Lost iron ore exports are offset by record coal exports. But Australian investors need to watch the Chinese economy, just in case it doesn't recover within six months. If so, there will be more negative consequences for the global economy. Funds operated by this manager: |

25 Oct 2021 - Manager Insights | Laureola Advisors

|

Damen Purcell, COO of Australian Fund Monitors, speaks with John Swallow, Director at Laureola Advisors. The Laureola Australia Feeder Fund has a track record of 8 years and has consistently outperformed the Bloomberg AusBond Composite 0+ Yr Index since inception in May 2013, providing investors with a return of 15.4%, compared with the index's return of 4% over the same time period. On a calendar basis, the fund has never had a negative annual return in the 8 years since its inception. The fund's largest drawdown was -4.9% lasting 10 months, occurring between December 2018 and October 2019.

|

25 Oct 2021 - Under The Microscope: Thermo Fisher Scientific

22 Oct 2021 - Webinar | Colins St Asset Management

|

Webinar | Colins St Asset Management Superior investment outcomes require thinking outside of the box, doing something that others won't so that you can achieve the type of returns that others don't. Since inception in 2016 the Collins St Value Fund has delivered a net return in excess of 19% p.a., over 8% p.a. higher than the broader Australian equities market through an unconstrained, high conviction Australian equities mandate with zero fixed management fees. During this webinar, Michael Goldberg, Managing Director and Portfolio Manager of the #1 ranked Collins St Value Fund (3 & 5 years by Morningstar) and Rob Hay, Head of Distribution & Investor Relations will share some insights into how 'special situations' have helped drive these returns, whilst seeking to preserve investor capital through asymmetric investment opportunities in convertible notes and take-over arbitrage strategies.

|

22 Oct 2021 - Are Bonds Really Defensive?

|

Are Bonds Really Defensive? Jonathan Wu, Premium China Funds Management October 2021

|

22 Oct 2021 - Why slow drivers are fools

|

Why slow drivers are fools Nicholas Quinn, Spatium Capital October 2021 "Anybody driving slower than you is an idiot, and anyone going faster than you is a maniac" - George Carlin. A few months back, my colleague Jesse wrote about the competing nature of the efficient market hypothesis and behavioural finance. Here's a brief recap:

Rereading this got me thinking about the active vs passive investing debate. In particular, how we might divide them into the two above camps and the similarity to George Carlin's infamous stand-up routine. On the matter of dividing them into camps, it seems that passive investing is more akin to the Efficient Market Hypothesis, given its implied nature of not seeking an excess (or outperforming) return. Whereas with active investing, this would better align with behavioural finance, as often the mandate is to seek outperforming investments. Unpacking this further, we know that in theory all publicly listed companies must distribute pertinent information to the market equally. Although in practice, we know that despite this dissemination, rarely is every page or slide considered prior to making an investment. Put another way, assuming all investors have the time to read and digest all available information, and process this information at the same rate, we would essentially all drive at the same speed and arrive at the same time. Behaviourally however, we know that human decision-making does not always follow the same logic, which may help fuel mispricing's such as market bubbles and exponential growth in speculative assets (such as cryptocurrency). Similar to when some drivers may be driving faster and more erratically than you.

It's little surprise that as investment managers of the Spatium Small Companies Fund, an actively managed fund that has outperformed the index by 10.8% per annum since inception (to 31 August 2021), our bias is naturally weighted towards active investing. However, parking that aside for the moment, there may be some merit to low-cost passive investing for retail investors, especially those who entered the market in 2020. A report out of the University of NSW highlighted direct stock ownership by retail investors (defined as having 1,000 or less shares in the ASX300) increased by 7% in 2020, whilst CNBC reported that an estimated total of 15% of all retail investors began investing in 2020. No doubt retail investors were, in part, motivated by the unprecedented rise in markets post the COVID-invoked bottom of 23 March 2020. To put this rise into 'unprecedented' context, the S&P500 has doubled in value from the 23 March 2020 bottom to 16 August 2021. Considering that it normally takes an average of 1,000 trading days (of which this time only took 354 trading days) for the market to double from a bottom (such as the GFC or World War II), labelling this rise unprecedented may be not giving it enough justice. Furthermore, as many global markets drove at similar speeds post the initial COVID shocks, it is easy to get carried away with the (false) assumption that past performance is an indicator of future performance. Especially for the retail investors that sought to directly invest in stocks throughout 2020, there may be those who are beginning to drive at different speeds relative to the broader market. This begs the question, if retail investors are finding their once 'speeding' portfolios slowing to a school zone pace, might they be better off driving at the same speed as everyone else in a passive product? It is hard to argue with the ease of access and diversification options that passive products can offer one's portfolio. Additionally, a retail investor can access these options easily and at a relatively low cost. That said, a word of caution on passive products; there is a growing criticism that passive investing is eliminating the need for price discovery or individual research at the stock level. The lack of price discovery in passive products may be driving markets to be more inefficient as opposed to serving the very camp that they belong to. Given the relatively recent trend in passive products over the past decade, the full ramifications of their impact on markets is still unknown - some industry heavyweights such as Michael Burry have even gone as far to say that when passive product inflows become outflows, "it will be ugly". Fundamentally, an investor's willingness to agree with one investment style or the other resides with internal biases and past experiences, notwithstanding that the available data on the ever-evolving allocation to passive investing is still quite premature. As such, an assessment on exactly how this will affect markets remains an argument for another article. Either way, as the debate rolls on, we encourage all readers to abide by respective speed limits (levels of risk), rather than focusing solely on an estimated time of arrival (target return). Funds operated by this manager: Spatium Small Companies Fund |

21 Oct 2021 - When Opportunity Knocks

|

When Opportunity Knocks Aitken Investment Management 29 September 2021 |

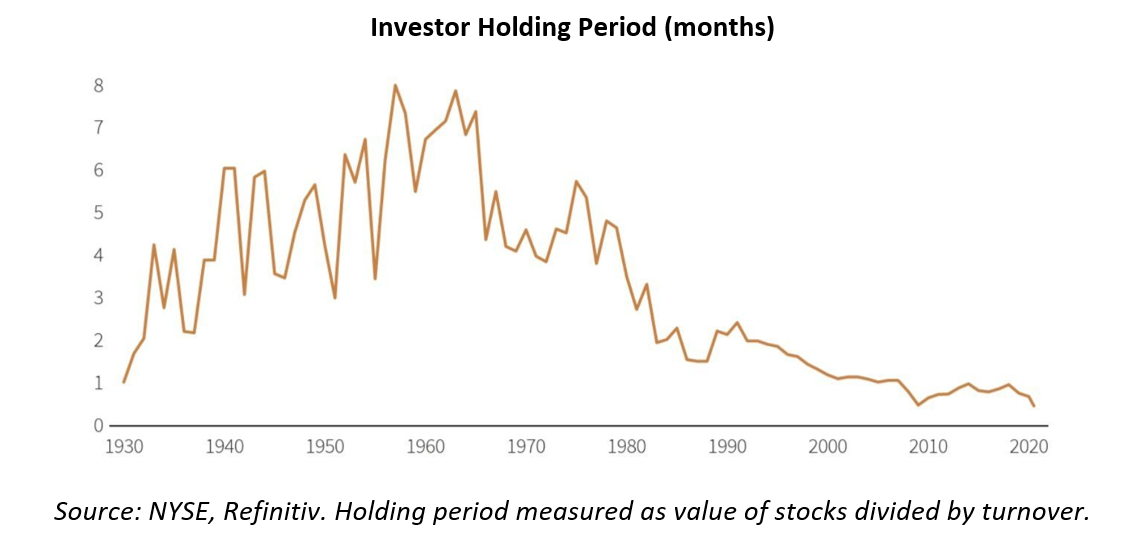

The Facts about Market TimingTo begin with, we subscribe to the view that the attraction of equities is the availability of compound total returns ahead of inflation over time. This comes with a cost: investors will only enjoy the effect of the compounding process if they remain invested for the medium to longer-term. An investor's friend is time, conviction, fundamental research and a business ownership mindset. Nevertheless, the temptation to 'take some risk off' is ever-present. While each individual investor will have unique circumstances driving their personal asset allocation, we don't attempt to engage in market timing within the Fund. (A piece of investing wisdom we take to heart is that there are two types of investors when it comes to market timing: those who cannot do it, and those who know they cannot do it). We believe that the reasons for market timing rarely working can be boiled down to two underlying issues: 1. The risk of missing out on big 'up' days can have incredibly negative impacts on long-term returns… and not surprisingly, the big 'up' days tend to be clustered around the big 'down' days during periods of increased volatility. Giving in to the temptation to 'get out' on the big down days dramatically increases the risk of missing the rebound. Many studies have borne this phenomenon out; according to a recent piece of research by JP Morgan Asset Management, $10,000 invested in the S&P 500 on 3 January 2000 would have turned into $32,421 by 31 December 2020 for an annual compound rate of return of 6.06%. Missing the 10 biggest 'up' days cuts that compound rate of return to 2.44%, while missing the 20 biggest days reduces it yet further to a paltry 0.08% per year. Missed the 30 best days? You would actually end up with less money than you started, having compounded at -1.95% per year for 20 years. 'Getting out' to avoid the psychological pain of short-term paper losses is not worth the increased risk of long-term damage to returns, in our opinion. 2. Markets are second-level systems. It is not enough to accurately predict an event; one must also correctly predict what the market was anticipating prior to the event and then correctly deduce how the market might react to the new information. We think that getting all three of those variables correct - and then being right on the timing, to boot - is nigh-on impossible to do repeatably. Since 1950, the S&P 500 has experienced 36 separate drawdowns of 10% or more. Ten of these double-digit declines ended up exceeding 20% (the popular definition of a 'bear market') peak-to-trough, while the other 26 ended up somewhere between -10% and -20% (a 'correction, euphemistically.) Statistically speaking, if there have been 36 double-digit drawdowns over the past 70-odd years, it works out that investors should expect this to happen with a frequency of about once every two years. Corrections and pullbacks are essentially an unavoidable part of the investment journey - and when seen in perspective as a period of prudent capital allocation with a margin of safety, is more likely to provide opportunity than lasting damage. Investor Time-Horizons: Shorter Than EverClosely linked to this point - using periods of market weakness to allocate capital - is the fact that investor time horizons have almost never been shorter. Based on an analysis of turnover, the average investor in US equities hold their positions for less than a year. As the chart above shows, investor holding periods have been steadily decreasing since essentially the early 1990's, meaning this dynamic is not a new one. Over the past 18 months or so, access to cheap leverage and commission-free trading has likely exacerbated the trend. We recently tested this thesis on some of the high-profile, high-growth businesses that have come to market since the start of the pandemic. After adjusting for management ownership and strategic investors, it appears to us that a number of businesses essentially see their free float turned over in full every two to four months. Keep in mind, this is for businesses where the drivers of value lie several years in the future. We have very little doubt that there is substantial short-term speculating about long-term variables occurring in the equity of certain businesses. Of course, shortening holding periods also create opportunity. If an investor can simply take a 12 to 18-month forward view, one is already looking out further than the majority of the daily activity in markets. (We generally try to formulate a view on a 3-to-5-year basis). When a high-profile business suffers the inevitable disappointment relative to the sky-high expectations embedded in its price, the pullback can provide a window to the patient investor. The narrative behind any pullback can be varied: stalled US debt ceiling negotiations, fears of a slowdown in China, rising energy prices, ongoing supply chains disruptions, resurgent COVID cases or lockdowns all seem like likely candidates. However, to the investor who takes a business ownership perspective and understands the quasi-permanent nature of equity ownership (particularly in competitively advantaged businesses), such pullbacks usually provide the time to wisely allocate capital. Getting scared off by a compelling narrative around risk is exactly what causes inactivity when the market goes on sale. The Psychology of Uncertainty -Prepare, Don't PredictFred Schwed Jr. was a professional broker active on Wall Street active during the crash of 1929. Several years after the event, he wrote the seminal Where Are The Customer's Yachts?, in which he provided a true, timeless and hilarious view on the inner workings of investment markets and Wall Street culture. Despite being nearly 100 years old, the observations in it remain timely, and we highly recommend it to our investors - it is a quick read, and extremely funny to boot. In Where Are The Customer's Yachts?, Schwed writes: For one thing, customers have an unfortunate habit of asking about the financial future. Now, if you do someone the single honour of asking him a difficult question, you may be assured that you will get a detailed answer. Rarely will it be the most difficult of all answers - "I don't know." We strongly agree with this statement. The one thing markets (and by extension, investors) hate is uncertainty. Uncertainty leads to volatility, which leads to those troublesome corrections everyone is trying to avoid. It is therefore no surprise that market commentators hold forth on a variety of subjects with great certainty: "inflation will do X", "the currency will do Y", etc. The problem is this: absolutely no one knows what will happen with 100% certainty. All of the knowable facts lie in the past, while all of the value lies in the unknowable future. Following the recent experience of navigating markets in 2020, one maxim of AIM's investment team is that among the four most dangerous words in investing (alongside Sir John Templeton's famous "this time it's different") are "we know for sure" - particularly when it comes to macro-economic prediction. Instead of selling you certainty, we believe in working alongside our investors to get comfortable in living with the psychology of uncertainty. Our motto in this regard: prepare, don't predict. We limit our predictions about the future to businesses we believe we understand, and by sticking to this circle of competence - and owning businesses with prodigious amounts of cash on hand and cash being generated - we believe we are prepared for the 'vicissitudes of fate' that will play out in the real economy. When we believe we have both an edge in understanding as well as a margin of safety, we prudently invest your capital, effectively handing it over to the right business managers at the right price. We believe this approach is likely to lead to far more beneficial outcomes over time than trying to predict and position for short-term macro-economic outcomes. Sustained, Incremental, SensibleAs exciting as it may feel to time the market, worry about every headline promising impending doom and trading in and out based on some forecast of an imminent correction (which may or may not happen), the evidence proves that such strategies rarely work. Instead, far more is achieved when sticking to a strategy that allows for the aggregation of small gains - in other words, compounding - to build up over time. Practically speaking, this means that most investors are almost always going to be better off by simply using a dollar-cost averaging strategy through time. By mentally sticking with an allocated amount to invest through thick and thin, investors generally do better over the long term than by making big calls to get in and out of the market. The reason is simplicity itself: this strategy keeps you invested - and more importantly, still investing - when the proverbial lean years come around in the market. (Logically, one may consider whether it is appropriate within their personal circumstances and risk appetite to accelerate such a strategy when market volatility offers a greater margin of safety when a correction (or bear market) does occur.) If the conclusion to this note seems somewhat boring, we have achieved our goal in writing it. 'Sustained, incremental and sensible' as a capital allocation strategy is hardly going to get the blood pumping on any particular day, but it makes all the difference when adhered to for long periods of time through the wonders of compounding. Through a number of market cycles, we have found that time in the market matters more than timing the market. |

|

Funds operated by this manager: AIM Global High Conviction Fund |

21 Oct 2021 - Our principles-based approach to Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG)

|

Our principles-based approach to Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Claremont Global October 2021 Growth in ESG awareness ESG awareness among investors continues to increase on a global scale. This has been made most evident via the growing prominence of the United Nations Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI) among institutional investors. Launched in 2006, the PRI was initially established to raise awareness of Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) considerations among the investment community, as part of developing a more sustainable financial system. Since that time the PRI has become the world's leading proponent of responsible investment and as of 2020 exceeded 3,000 signatories and represented over US$100 trillion of assets under management.1 PRI signatories and assets under management (AUM) Alignment with our investment framework With a central focus on sustainable long-term company performance, the Claremont Global Fund is now a signatory to the PRI. Whilst a new and welcome development, in reality we expect there will be little change to our proven investment process. Our underlying strategy and our rigorous research-backed process naturally leads to investment in well-run businesses with strong management teams and a culture attuned to the long-term needs of all stakeholders. Since the inception of the strategy in 2011, our goal has been to generate returns of 8-12 percent per annum, through the cycle, for our investors. We have always stressed to clients the importance of keeping a long-term perspective. Our ability to achieve this requires us to remain true to our investment process and invest in sustainable businesses - something we believe is largely unachievable, without serious consideration of ESG principles. Research has shown that when companies adopt good ESG policy it's a positive for all stakeholders, which includes improving financial performance for investors.2 Relationship to our investment pillars Our philosophy and process are based on four key investment pillars: ESG considerations comprise an important part of our research on the first three pillars when we analyse a company to determine its investment suitability. Notes: 1. Principles for Responsible Investment, "an investor initiative in partnership with UNEP finance initiative and the UN global Compact", 2020 Management quality and ESG We believe that a first-class ESG approach is unlikely to have a tick-the-box methodology. Rather, it is driven by the principles, values and, most importantly, actions that underpin company culture. This flows from the actions of management and the board of directors - with management quality one of the fund's key investment pillars, (or in ESG parlance, a focus on good governance). This requires a long-term mindset; a focus on delivering value to customers; equitable treatment of employees and communities; and continuous operational improvement that benefits all stakeholders. Our experience is that this long-term mindset is typically found within stable, well-tenured management teams - it is unlikely to be built overnight - and is something we seek in all the companies we invest. However, culture is more difficult to measure and requires some judgment on our behalf. With a relatively finite universe of companies that meet our quality investment criteria, we can consistently engage with management teams, allowing us to better assess management's mentality and actions, and gain deeper insight into the prevailing culture. Prior to investment in a company, we will always speak with ex-employees, competitors and industry experts where possible. We also look at the composition of the executive team and board, tenure and strategy. This, we believe, allows us to pass both an independent and educated judgement on a key facet of a business that cannot be screened for, lifted from a broker report, or extracted from an ESG score from one of the rating agencies. Capital structure and ESG A strong balance sheet - another of our key investment criteria - is often illustrative of good governance, and is an area frequently overlooked, due to a focus on maximising short-term profitability. Companies that engage in 'financial engineering', such as taking on excessive debt to reward shareholders in the short-term, through share buybacks and poor M&A - only to then go seeking government and/or shareholder assistance in times of crisis - is in our eyes a complete governance failure. Our process deliberately aims to keep us clear of such businesses and industries, allowing us to research and ultimately invest in businesses that are managed to successfully navigate, and indeed prosper, through adverse economic events. The average age of the companies in our portfolio is currently over 80 years and these businesses have seen many economic cycles and stood the test of time. Their durability is a combination of tested business models; the value proposition they offer their customers and employees, and prudently managed balance sheets. It is difficult to overstate the power of incentives and we always analyse management compensation closely. We engage with our companies regularly (at least quarterly), highlighting what we believe are important considerations, as well as voting on the remuneration of executives on an annual basis. Incentives for some companies are skewed to short-term financial metrics (such as "adjusted EPS") and a misaligned remuneration structure may lead to short-term gains, but result in perverse outcomes both for the broader community and ultimately for the longer-term shareholder. When considering the Environmental impact of a business, we find that management teams with a strong culture and good ethics, coupled with the right incentives, are comfortable investing in areas such as energy and water efficiency, waste reduction, and/or proper remediation of historical environmental issues. These investments can often have a negative impact on short-term profitability but deliver long-term benefits, ranging from reduced carbon emissions, employee safety, favourable reception by local communities, regulators, and customers - all while reducing operating costs over time. As a result, we prefer to see a large proportion of management compensation based on a variety of long-term metrics such as organic growth, margins, cash flow and return on invested capital, rather than measures such as "adjusted" EPS, which can be more easily manipulated in the short term. Business quality and ESG Of course, a definition of business quality is broader than simple financial metrics. In the past, Social issues may have been limited to the human resources division, however, today they expand far beyond this narrow remit. For us, social considerations cover the relationships the company has within its ecosystem. From the impact the company's products/services have on communities, to the treatment of their employees, places of manufacturing and suppliers. We have no doubt that failure to adequately respect all subsegments of a company's value chain will impair the long-term sustainability of a business. Globalisation, transparency, investor awareness and ESG are increasingly (and rightfully) calling into question how a company's profits are made. We routinely engage with management to better understand whether they may be compromising on the quality of their product/service (for example, buying materials from a cheaper source that does not adhere to local emission or labour practises) to simply meet a short-term financial objective. We believe such actions are not sustainable over the long-term but also highlight management's failure to seriously consider the impact of their business on society and the culture of the organisation. Identifying quality growth businesses for the long-term Despite the best intentions, the rise of ESG within the investment community has not been spared the hype that generally accompanies an emerging area of interest where financial gain is possible. Increasingly, the industry is looking to capitalise on the trend, launching 'green' funds (which often come with higher fees), while investors have looked to profit from the share price appreciation of companies they think will be beneficiaries of ESG- focused buying. With a clear focus on capital preservation, investors in our fund can take comfort that we will remain disciplined when it comes to the price we pay for businesses and exercise caution by avoiding areas of speculation and thematic investing. As illustrated, the principles of ESG have been - and will continue to be - critical to our investment process and our portfolio of companies. However, ESG factors are nuanced and typically cannot be reduced to specific metrics or rules that are comparable across businesses. As a result, we believe it is prudent to use independent judgement and consider each business on a case-by-case basis, rather than be governed wholly by externally generated ESG metrics. To conclude, whilst ESG in the mainstream is a relatively new phenomenon, our investment process has always emphasised management teams with a strong commitment to their customers, employees, communities and wider society. We believe when these factors are combined with good governance and prudent balance sheets, the end result is better risk-adjusted outcomes for long-term shareholders like ourselves. Funds operated by this manager: |

20 Oct 2021 - Manager Insights | Aitken Investment Management

|

Chris Gosselin, CEO of Australian Fund Monitors, speaks with Charlie Aitken, CEO & Portfolio Manager at Aitken Investment Management. The AIM Global High Conviction Fund has been operating since July 2019 and has delivered investors an annualised return of 17.30% since then vs the Global Equity Index's +14.83%. These returns have been achieved with the same level of volatility as the market. Its capacity to outperform on the downside is supported by its down-capture ratio (since inception) of 83%.

|